Senza Titulu: Solo Exhibition by Raymond Minnen

Senza Titulu, the title of Raymond Minnen’s solo exhibition in Everyday Gallery, apparently contains a typo. In reality, it is a willful and playful way to disrupt the meaningless Italian Senza Titolo (untitled), so often found in abstract paintings from the 1970s. It is emblematic of Minnen’s artistic approach: many of his works are seen to be a little naive, but the opposite is true, he unleashes small shifts in the meaning of a word or a symbol that have far-reaching consequences. This is often a way of questioning the existing order or criticizing power.

Raymond Minnen was born shortly after the Second World War into a working-class family in Balen, in the southern part of the Kempen. Apart from a short study period in the city of Antwerp at the end of the sixties, he spends most of his working life in his home region. The region has played an essential role in his work since the 1980s. At that time, Minnen developed a unique visual language that enabled him to provide an artistic commentary on the world at the end of the Cold War and on the region in which he is rooted. Humor and feigned naivety are important elements for providing social criticism.

A good example of this is the series The Desert After the Storm (1992). At first sight, we see a series of fuchsia pink and lemon yellow chocolates. Some bear the insignia of a crown, a heart, or a butterfly - but all have melted. However, if you look closely, you will discover an acorn and a nipple in the series. Subtly tucked away, we find here a nod to the sensuousness and oral pleasure that is so characteristic of humans, but which we also like to tuck away.

Minnen often works with materials that he gets from everywhere and nowhere, and they regularly come from local newspapers or thrift shops. That’s no coincidence. It regularly concerns materials or objects that have circulated around the world; then those materials are combined with highly local elements. In this way, Minnen weaves together the global and his own Heimat. The ironic criticism that arises is often caustic and always prompts reflection. In Ancestors of the Dobakola, for example, Minnen works with an East African image he found in a trinket shop. A cuddly giraffe is attached to the head of the statue. If you look closely, you will understand how sharp Minnen’s critique of our colonial view is: that an image can circulate so easily and without documentation in a Belgian trinket shop says about how our colonial past (including looted art) still affects the present, and that applies just as much to an exotic stuffed giraffe retrieved from a toy store. By bringing the two together, Minnen constructs a social critique that is humorous and wry at the same time.

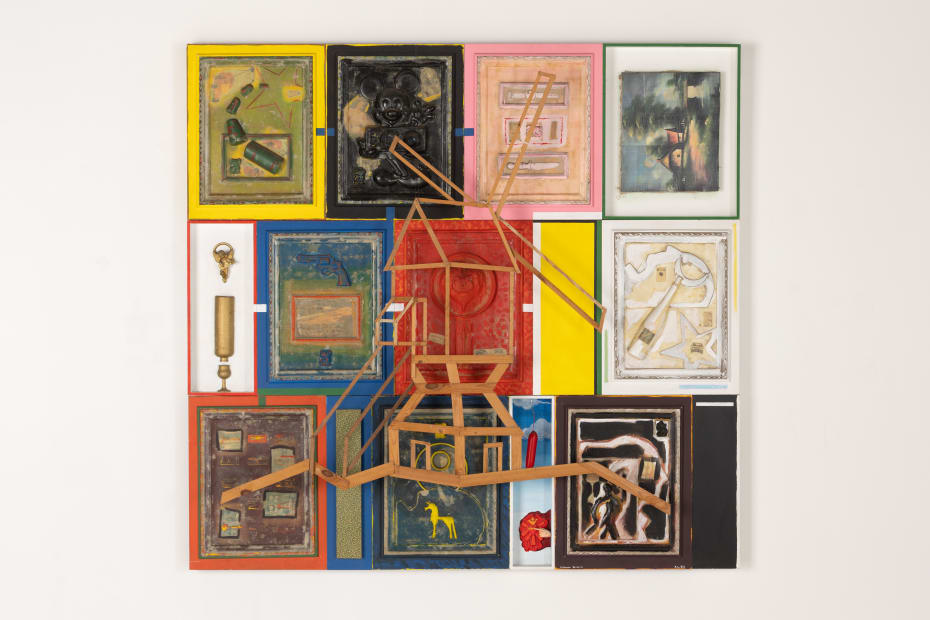

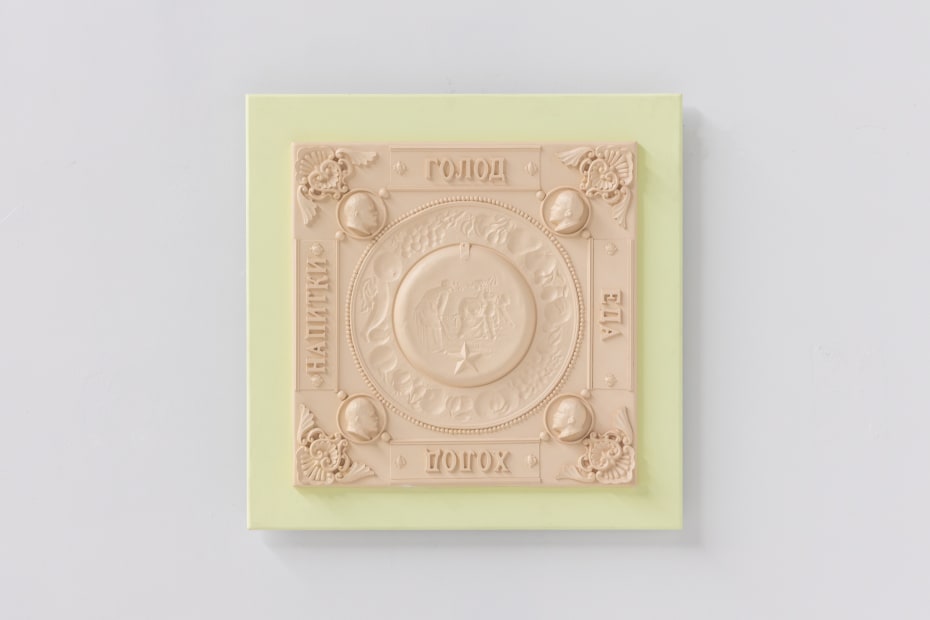

With the same social-critical view, we find ourselves back in the assemblages Lichtenstein in Neuschweinstein and Monument to the Brandenburg Gate (both 1995), which provide a commentary on the unified Germany and the end of the cold war. Even after the fall of the wall, the (now discarded) statues of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin begin to circulate in the West. They turn up at scrap dealers, trinket shops and antique dealers. The fact that a political leader who was once revered and worshiped by almost the entire leftwing in politics is now despised, cast aside and can be bought in thrift stores, is reason enough for Minnen to start playing with this figure. In ‘Op Avontuur met Lenin’ (2016) he does not portray Lenin as a sort of Tintin-like adventurer who played a relevant role during all sorts of essential moments in decolonial and local history: from the

independence of Congo to an important strike in his own village Balen. Ridiculous, of course, but Minnen’s point is a strong one: political fictions like this have shaped our political history for centuries.

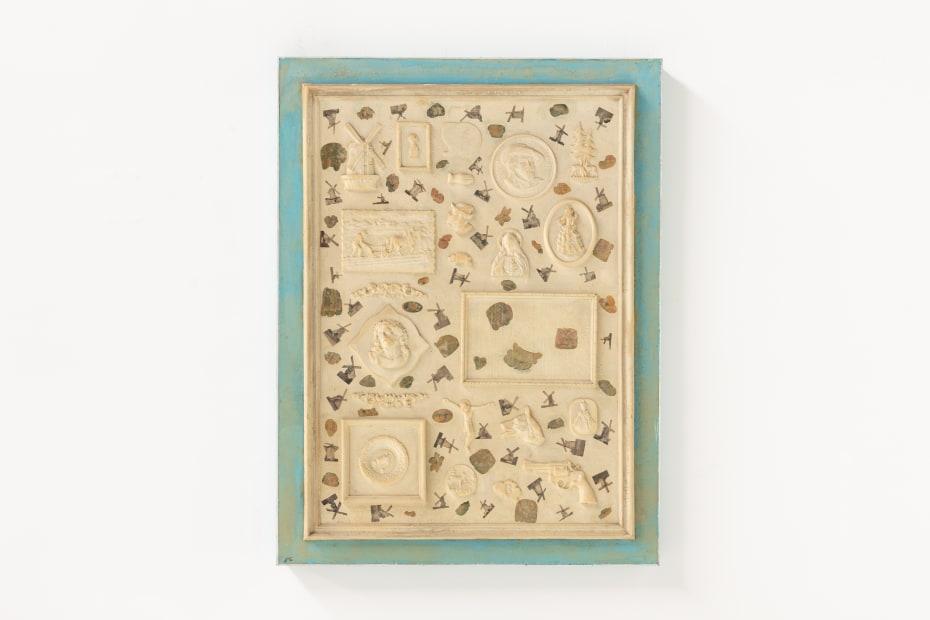

That is what the Kempisch Landschap series is all about. Minnen spent almost his entire life in the southern Kempen. In Kempisch Landschap he plays with some of the typical symbols of the local culture, often from agricultural tradition and Catholic history. The most eye-catching is probably the windmill. Once upon a time, the mill was really part of everyday life, but today it mainly serves as a folkloric symbol. Minnen comments on a reality in which life has been detached from religious rituals, great political ideologies, and rooting in the earth, but what has replaced it remains unclear.

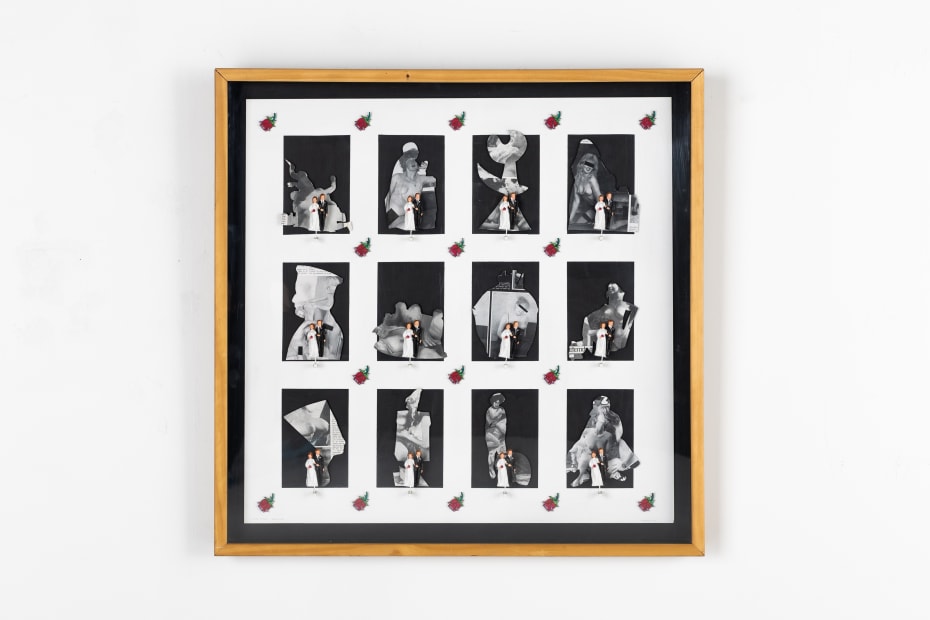

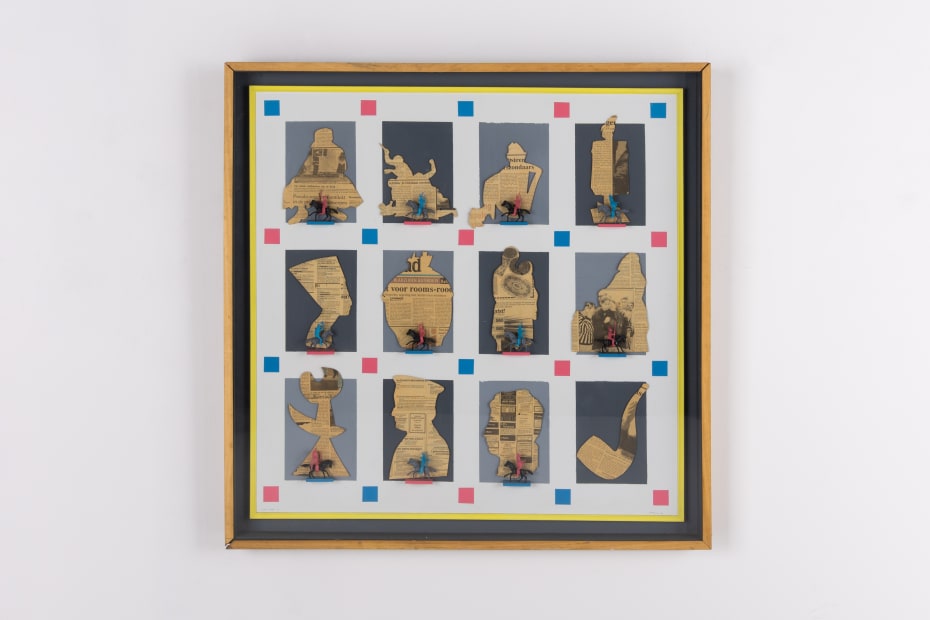

What is certain is that Minnen is always out to dismantle power itself. Sometimes that is the power of rituals and folklore, sometimes the power of politicians or religious leaders. And often that dismantling takes place through a shift in meaning. In the Senza Titolo series, this is done by showing well-known profile views of religious and political rulers as part of a collage. They are cut from telling pieces of a crate that subtly contradict their power, on a photographic background that sharply contrasts what these so-called political leaders stand for or steam.

In this way, Raymond Minnen builds up an oeuvre in which a clash of worlds is always imminent. They are often clashes that he has personally experienced in one way or another because he too is a child of history.